Part 2 (deux?)

What’s sort of been lost to history is that World War I came within a Kaiser’s eyelash from starting almost exactly 3 summers earlier, in 1911. Seems that the French and Gemans got themselves into a nasty diplomatic tussle over Morocco. The North African country had been sort of independent for a while, but had always been regarded by the French as their own little protectorate. The Germans decided to push that issue with some gunboat diplomacy after a minor rebellion in the country. The idea was some harebrained notion by the Kaiser’s ministers to try to drive a wedge between the French and English, who’d entered recently into an uneasy entente (at this point in history, it should be noted that the English still pretty much hated the French and everything they stood for…but they made a convenient ally against a frightening Germany who was building a navy and catching the Brits in an arms race.)

If they could, the Germans also wanted to use the lever of threat in Morocco to get the French to cede them some of their colonial possessions in the heart of Africa.

The two countries walked right up to the brink of war that summer. The Germans and French were both thisclose to mobilizing, which would’ve caused the Russians to mobilize, which would’ve caused Austria Hungary and Italy to join Germany in mobilizing, and grab your ankles and kiss your ass goodbye, Europe.

It didn’t happen, though.

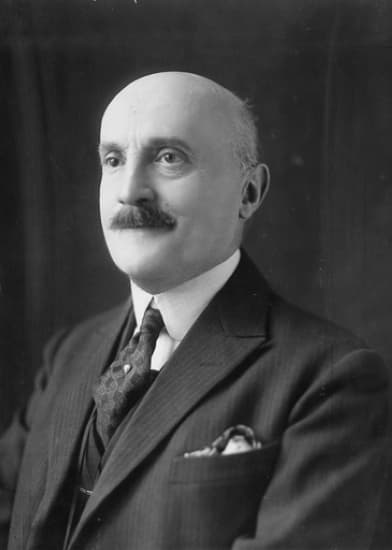

France was blessed with one of the most politically adept Prime Ministers since becoming a full-fledged parliamentary republic. Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux was a waspish, bespectacled and button-down sort who was actually an accountant who’d made his name in the Ministry of Finance. Caillaux quickly deduced that the Germans were bluffing, and refused the calls by his General staff to declare war and mobilize. Instead, he pulled off some seriously Cold War style diplomatic magic. He negotiated a settlement that gave Germany nothing it wanted, and got France to come out ahead. He offered to not contest German claims on the African state of Kamerun (World Cup fans, that’s Cameroon to you). He also tossed in some middle Congolese lands, which he’d already figured out were never going to be useful to France. Enjoy that jungle marshland, Fritz.

He also got Germany to agree to a renewed French claim once again establishing Morocco as a colony and protectorate of France. (Score!) It also turned out that England was pretty pissed with Der Kaiser, and this nonsense only strengthened the the alliance between Britain and France. (Score again!)

For all that, Caillaux was excoriated in the press, dominated by conservative, war-mongering voices. He’d capitulated to the Germans, in their view.

It was nonsense, but Caillaux had made himself no friends with the conservatives who still held sway in French government and dominated the press (especially in the paper, Le Figaro).

(Joseph Caillaux)

See, even though he had a conservative, accountant’s upbringing, Joseph Caillaux was a pragmatist. He’d taken a look at the French economy when he was Finance Minister, and realized that his country was headed for some serious feudalism, creating a permanent majority of an impoverished population. The only way out of this horrible outcome he decided, was to do what was working so well for the Americans across the pond. France needed an income tax.

Caillaux’s fellow conservatives were horrified. Instantly the Finance Minister was branded a socialist (sound familiar?) However, in early 20th century France, that wasn’t such a bad thing. Socialism was a movement on the come, gaining wider and wider influence in French politics, faster and faster. At the head of the movement was an affable, bearded movement leader named Jean Jaures.

(Jean Jaures)

It’s tough to find an analogous modern character for Jaures. Imagine, I guess, if Jon Stewart was even more influential, ran his own newspaper, and was generally loved even by those who hated his politics. That’s Jean Jaures. Everyone loved the dude. He was also considered the best public speaker in all of Europe and perhaps the world. He was a socialist and stern pacifist.

Caillaux was forced from office after the conclusion of the Moroccan affair, and switched party allegiance. Jaures realized that Caillaux wasn’t a perfect socialist, but he was better than anyone else who might someday be Prime Minister again. A little bit of politics and strange bedfellows, a little bit of the enemy of my enemy is my friend going on. Jaures threw his socialist weight behind Caillaux. And then, to the surprise of many, the socialists started winning more and more seats in parliament. Caillaux began a gradual re-ascension to power heading towards 1914.

In the winter of 1914, the socialists and a coalition of other so-called radicals seized a plurality of the house of Parliament that got to choose a Prime Minister. Joseph Caillaux was once again in his familar position as Minister Of Finance. It seemed a certain deal that he would once again be Prime Minister.

That would work out so well for the troubled times coming. The pragmatic Caillaux would’ve almost certainly told Tsar Nicholas to check himself, because France had no intention of supporting him if he dared to mobilize his army. Caillaux would’ve likely told the Serbian nationalist terrorists who thought they could count on French financial and military support that they were out of their freaking minds, and would’ve denounced them. He’d have been on the phone to German diplomats, and together they’d have calmed the Austrians the hell down.

There was one problem with all that, though.

Joseph Caillaux, for all his political effectiveness, had a weakness for the ladies. Bigtime. He’d carried on an affair with a married woman who’d divorced and then married him. As soon as they married, Old Joe decided he needed a new mistress, and took up with another married woman. After a few years, both Caillaux and his new mistress divorced their first spouses (SCANDAL!) and married. That wasn’t enough of a scandal to keep him from being Prime Minister, though.

However, the first Mrs. Caillaux (who’d also divorced to take up with the womanizing accountant politician) was understandably bitter. The conservative enemies of Caillaux sought to exploit that, and she was happy to oblige. She sent some love letters Caillaux had written her when she was still married, at the start of their affair that led to his first marriage, to Le Figaro. The conservative paper published the “juiciest” letter of the lot, which ended up being dull as dirt. (The biggest scandal was Caillaux’s usage of the pronoun “ton”, which was a bit overfamiliar for the time; the rest of the letter was him prattling on boringly about land tax policy. No, really.)

When that letter failed to arouse much interest, Le Figaro’s editor, one Gaston Calmette ('member him?) let it be known that perhaps there were more letters.

Well.

The newest Mrs. Caillaux was having NONE of that. She was headstrong and proud, and hated to think what might be in those unreleased letters. It would damage her husband’s political career, and it would certainly damage her already frayed social standing.

So…yeah. You’ve probably guessed that the Lady Henriette’s last name was Caillaux, and she was the second wife of the likely next Prime Minister of France, Joseph Caillaux.

And yes, she did indeed assassinate the editor of the paper, and all of Paris was abuzz in late June of 1914, awaiting the start of the trial.

For his part, Joseph Caillaux decided his political career was over and resigned as Finance Minister. The conservative French President, Raymond Poincare, helped pick a “socialist” replacement, Rene Viviani, who rapidly turned into a puppet of the conservatives, much to the outrage of Jaures.

And, thus and so, one of the persons who likely could’ve hit the brakes and prevented the onset of war was removed from the picture over a romantic scandal and a crazy wife.

It happens.

Tomorrow: You say terrorist, they say secret society.