The Watergate 7 Go On Trial

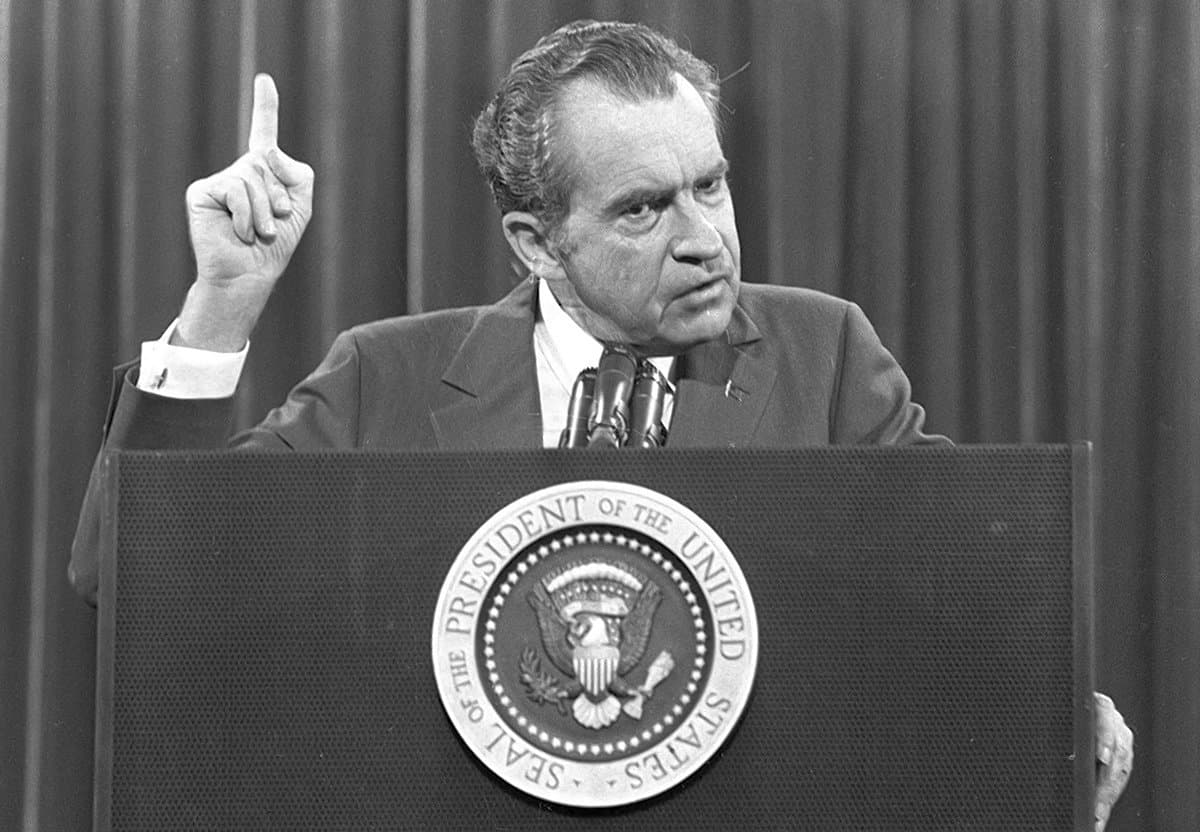

It’s January 10, 1973, and Judge John Sirica finds his courtroom to be absolutely packed as the trial of the five Watergate burglars and their two planning accomplices go on trial. And so on January 9th while Nixon was enjoying the reverie of his happy birthday and seemingly ascendant presidency there are a couple of things he was not aware of that probably would’ve put a real wet blanket on things.

First, he and his inner circle (and honestly most politicians across both parties in Washington) have, far, far underestimated the curiosity of Americans with regards to Watergate. Yes, no one paid a bit of attention to Watergate when they voted for President in November. But the public interest in the scandal feels like kind of a unique moment in US history.

It’s as if the country collectively decided to put a pin in the scandal. They didn’t want to vote for McGovern, and besides…it just seemed crazy that the higher-ups at the White House would be involved in this kind of stuff. Kind of a case where people really did want to accept the Occam’s Razor explanation: it was far more conceivable that the Watergate break-in was some rogue element of the fringe end of the campaign acting on their own without authorization. It just made no sense that Nixon or his campaign or the White House would get involved – everyone had known for over a year that Nixon was going to coast to victory in 1972.

But that didn’t mean there wasn’t any interest in the scandal. People absolutely wanted to know just what the heck was up with that break-in that didn’t make even a tiny bit of sense. They wanted it sorted out for them.

And news media was happy to step in and do that sorting out. The Washington Post investigatory reporting by Woodward and Bernstein had raised the profile of that once sleepy hometown paper. But they’d so dominated the reporting that other news media just sort of stood on the sidelines.

The trial offered what appeared to be at least a quick, last chance to jump back in. And so all three major news networks in the US – and PBS – were in. So too were the AP, UPI, the LA Times and Wall Street Journal, amongst a host of local newspapers across the land, as well as Time and Newsweek, the two major news weekly magazines. (It’s hard to overemphasize the reach of Time and Newsweek at the time; a huge percentage of homes in suburban American in the 1970s were subscribed to one or the other.)

And finally, the venerable and influential New York Times was back in on the story, and in a big way. The Times had assigned young, renowned reporter Seymour Hersh (who’d broken the My Lai massacre story) to the Watergate beat.

Thus and so, if Nixon and his advisors had realized this, it’s likely the President’s birthday might’ve been a more somber affair. There was another thing the President didn’t know – but that White House Counsel John Dean and Chief of Staff Haldeman both did know, and hadn’t told him yet.

Maximum John

A week before the trial, Judge John Sirica had obliquely laid out some points of interest for the lead trial lawyers of each of the accused. The judge had seen enough evidence in the grand jury phase that he didn’t much care if everyone pleaded guilty or not. He wanted that evidence presented in open court, so if everyone copped to guilt, he was going to make sure that the sentencing hearings last weeks so that the evidence could be presented there.

Sirica was convinced that the things went far further than the seven men who’d stand trial in his courtroom in a week, and watching the grand jury process play out, he was spectacularly unenthused by the job done by the three lead prosecutors in the US Attorney’s office. Sirica told the attorneys (and the prosecution team in a separate meeting) that all he’d read about was how tightly and centrally controlled the Nixon campaign was. Therefore, it was beyond belief to him that somehow a rogue operation with no support elsewhere in the campaign had somehow got its hands on a quarter of a million dollars of campaign funds to commit the break-in with.

What none of the attorneys knew for sure – but sort of suspected, was that the judge was going to pull one of his tried-and-true maneuvers from the deck. Sirica, whose well-earned nickname was “Maximum John” for the sentences he often handed down, was going to use a trick from his playbook he’d used with organized crime, gambling, and racketeering. What Sirica would do is this: First, regardless of plea of guilty or not guilty by any defendant, Sirica was going to hand over maximum sentencing penalties for any guilty parties.

But there was more. The next twist in this playbook was that Sirica was likely to then inform the sentenced defendants that he’d happily stay in communication with the Bureau of Prisons. If any of them wanted to speak up and tell the court MORE about Watergate, the Judge was happy to hear them, and would then reduce sentences according to the value of the information and cooperation received.

Now, if you’re thinking that this sounds kind of legally dubious…well, join the club! Sirica’s application of some loopholes in the criminal courts here have been the subject of wonky legal debate since 1973, and will likely be a source of debate far into the future. Technically, his scheme was allowable, but it raises all sorts of issues of ethics and morality and judicial overreach. In the end, I’ve read a lot of legal opinions that say that what Sirica did here was fairly over-the-top…but also maybe in this SINGLE case, justified. Sirica likely suspected that the prosecutors were acting on instructions from above to not pursue the case past the 7 defendants, and in those extraordinary circumstances, perhaps extraordinary practices were required to expose the truth.

The thing of it is, should that all play out (and it will, spoiler) none of it will take the White House advisors by surprise. Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Dean suspected Sirica might be planning to do something like this. Hence, the Nixon plan of paying off the accused and their families with financial support, followed by what until now had been some vague promises of clemency or pardons came to fruition, to take the sting out of any penalties the judge might sentence the seven men to. And after communicating through an intermediary, as far as the White House advisors knew, their wall was holding; that solution worked for the Watergate 7.

Barker, Gonzalez, Martinez, and Sturgis (four of the five burglars) were represented by one attorney, and he let the White House team know that his clients were willing to do their prison time if the promises of financial support and eventual pardons was concrete. Some of those men had seen the inside of Cuban prisons, after all. If another undercover promise of incarceration at the posh, minimum security facility in Danbury, CT was forthcoming, no one was too worried about it.

E. Howard Hunt’s attorney reported that his client would play ball as well. Hunt was still deeply in despair by the world collapsing on him so suddenly since June of 1972. If financial support for relatives who’d have to care for his kids was coming, he was happy to try to make everything go away and vanish into a short prison sentence.

So that’s 5 of 7.

G. Gordon Liddy was the oddball in the group, as usual. His attorney informed Haldeman and Dean that Liddy had no intention of doing anything besides pleading not guilty.

But it’s not what you might think! Liddy – convinced as ever that he’d acted as a patriot in the best interests of his country to try to commit election fraud – was eager to plead not guilty so that the prosecution would be forced to show the evidence against him. Evidence that Liddy believed would show his heroism off to the American people. Gordon had zero intention of telling anyone anything about the operation itself, or who might be involved, or where the money came from. He wasn’t going to cooperate in the least, and he welcomed a stiff prison sentence with an enthusiasm that was kind of disconcerting. But hey, no interest in cooperating with anyone.

So that’s 6 of 7 bricks in the wall. But that 6th brick means that no one will have to wait for a sentencing hearing to get the evidence into open court, either. There will be a trial in the case of Liddy.

But then there’s James McCord.

McCord kind of doesn’t fit with the other 7 accused. While he’s a Republican who was happy to support Nixon, he’s not one of the wide-eyed true believers he’s accused with. McCord took the job with CREEP because the campaign needed a security expert (which McCord was) and because McCord’s friend Jack Caulfield put him up for the gig. And then things got carried away. You know how it goes: one minute you’re at your desk approving trip itineraries, the next you’re putting tape on a door lock at the DNC Headquarters.

McCord has his own legal representation, and the Nixonites already know he’s the weakest link in their strategy. The ex-CIA security expert has a young family at home, and he’s in no good mood to do an extended hitch in prison. Still, he’s signaled he’s willing to play ball, and Dean thinks he’ll be OK. McCord doesn’t really want to cooperate with prosecutors, for one thing. And if he gets the right assurances on financial support – and an eventual pardon, it’ll all be good. (Jack Caulfield is Dean’s go-between with Dean and McCord. Caulfield and McCord go on some long walks to the middle of bridges in DC where they can talk without any surveillance being possible. At one point, McCord pointedly asks Caulfield if the person making the offer of a pardon knows the difference between that and clemency. It’s super-important to McCord.)

For now, McCord is dithering on his plea, but he’ll go with not guilty to start off with, since Liddy is doing so as well. McCord’s attorney, Gerald Alch has told McCord to take any deal he can get, in the meantime.