I’m loving this retelling and all the treatments Watergate has been getting on this anniversary. I’m hoping all this sparks renewed interest into Nixon and more content is created that illustrates what complete and utter crooks Nixon and his administration were.

I was born just after Watergate, so obviously have no memory of it. But Chuck Colson had a regular show as a conservative talking head on evangelical radio when I was growing up. I knew him as a radio guy before I ever understood he was connected to Watergate.

I remember that Colson played the part of a born again Christian after he got out of jail. Whether he was sincere or not I have no idea.

This is sort of the embryonic modern version of "extremism in defense of liberty is no vice’ strain of American politics. No matter how batshit crazy and divorced from reality any of the things these people were doing, at some basic level it started with the belief that they were on the side of the angels "Occupation? “Anti-Communist!”) and engaged in a struggle to the death with the arch fiend. That informed all of the calculations at some Ur-level, even though pretty soon it all became ego trip and self-centered power grabbing and all that.

Americans though have a propensity for messianic, apocalyptic eschatology in their political and moral worldviews, and hey, if you can sneak in a bit of self-aggrandizement, well, why shouldn’t the holy warriors get their 72 virgins a bit early?

So it’s the morning of Tuesday, June 20 1972. 50 years ago today. And today is a hugely consequential day…and it’s a story that I’ve only seen told in a few places – Jimmy Breslin put it in his post Watergate book in the mid-1970s, and Garrett Graff references it in his new Watergate history. But first, John Dean…

This Cover-up Will Be Easy

John Dean has his plan of attack now. He’ll simply get the FBI to stand down by telling them that the Watergate break-in was probably a CIA operation – Cubans were involved, after all! – and that will be that. He picks up the phone to call acting FBI director L. Patrick Gray. Gray had been the acting director for all of about 2 1/2 weeks – named to fill the position after J. Edgar Hoover had died in his sleep in late May.

If it were any other job in government, or if you needed someone to run as a senator or governor, man did L. Patrick Gray have himself a resume to die for. He attended that Naval Academy at Annapolis, and was a star quarterback for the football team. He did five sub patrols in the Pacific during WWII. He commanded a sub in the Korean War, becoming one of the youngest captains in the Navy. He earned a law degree, and was a liaison between the DoD and the Department of the Navy. And then he went into private practice at a prestigious Connecticut law firm, until – as a loyal Nixon supporter from the get-go – he was offered a job at the Department of Justice. He’d been the associate Attorney General for civil affairs under John Mitchell – and was the first choice to succeed Mitchell in 1972.

And despite all that: L. Patrick Gray was in way, way, way, way over his head.

Unlike his associates at the FBI and in the criminal divisions of the US Attorney’s office, he’d never really practiced criminal law, and had certainly never worked as a prosecutor.

As things play out, L. Patrick Gray is going to stumble, idiotically and clumsily, into the middle of the cover-up. But on this fine June morning in 1972 and on the phone with John Dean, things go OK for him.

Dean, feeling all chipper and happy, greets Gray and asks him how he’s settling in at FBI. Gray and Dean make some small talk. They’re both loyal Nixon guys, for sure. Finally, Dean gets to the task at hand.

“Pat, there’s been some concern expressed over here about that crazy Watergate thing over the weekend. All those guys and their connections to the Agency and they’re Cubans…there’s some worry that we might be running right into an op, if you know what I mean.”

Gray’s voice on the other end of the line brightens. “I know exactly what you mean, John,” he says. “We’re on the same page about wanting to keep from bumping into the CIA on that.”

Pretend you’re John Dean for a moment, hearing that Gray is on the same wavelength and happy to play ball. Imagine thinking about how easy it is to serve the President at the White House. Nixon may not know your name yet, but when he hears how you’ve just shut down the Watergate investigation, you’ll be sitting with your feet up in the Oval Office, smoking cigars and sipping martinis in no time! What a cushy job!

“Yep,” says L. Patrick Gray. “We had the same thoughts over here as you about this maybe being an op.”

“That’s great, Pat.”

“So anyway, because of that,” Gray continues “I just got off the phone with (CIA Director) Dick Helms right before you called. He says he doesn’t think it’s them, so we’re full speed ahead over here.”

And just like that. Dean, his heart getting heavy, thanks Gray for his time. So much for easy.

Dean will report this to Haldeman and Ehrlichman shortly after the call. Those two, along with Nixon, haven’t given up yet on the “Let’s call it CIA” aspect and will revisit that later in the week.

In Brooklyn, A Butterfly Flaps its Wings

Also on Tuesday, June 20 1972, one of the most important (though no one would realize it for months and months) pieces of the enter Watergate affair fell into place.

So stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a telegenic, perky, highly energetic 30-year-old woman working as a parks department administrator decides that it’s time to challenge the incumbent representative to the House in a primary. We know that script, right?

Or try this out: that same young woman decides that the guy who’s been the representative in her district is no longer serving the needs of the shifting demographics in the area, and decides to challenge him in the primary, and then works like hell at the grassroots level to try to pull off an upset for the ages.

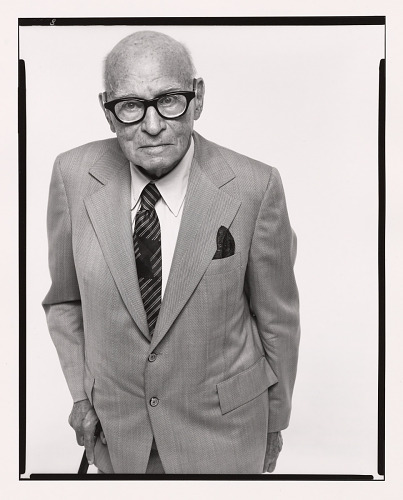

Hey, we all know the Leslie Knope story, and the Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez story. But before them and leading the way in 1972 was Elizabeth Holtzman.

Her Brooklyn district had been represented since the Harding Administration by Emanuel “Manny” Celler, who by 1972 was the dean of the House of Representatives in DC, and the senior Democrat there. Manny was an old school progressive, a loyal New Deal Democrat (literally, he’d been in congress for 10 years when FDR was inaugurated). As the longtime head of the House Judicial committee, he’d worked vigorously with LBJ to get the various civil rights and voting rights legislation of The Great Society passed.

In a lot of ways, Manny Celler was a pretty good guy.

(Manny Celler, circa 1972)

But he had his blind spots too. One was that in a more collegial atmosphere in the House, where there was still a liberal wing to the Republican party and a conservative wing of the Democrats…Manny just hated Republicans. And he really hated trying to cut deals with them. And that hate got worse and worse the older that Manny Celler got.

And while I’m guessing a lot of you are kind of loving Manny Celler for that here in 2022, his stridency was beginning to become a real problem by the late 1960s. Typically, some good piece of legislation would come to the Judicial Committee, and Celler would just run roughshod over the committee debate itself. He’d be uninterested in making even trivial changes to the bill to attract GOP votes in the committee, he’d cut debate time, and he’d denigrate even liberal Republican voices. And so the committee vote would end up a partisan split with no Republican support at all. And then the bill would die on the House floor with the conservative Democrats refusing to go along with it due to that committee split.

And when fellow Democrats on the Judicial Committee tried to suggest to Celler that maybe he might consider easing up a bit to get winnable Republican votes on board, and ask him why he was so strident and antagonistic, Celler would respond with language something like this:

Celler was used to winning his seat in the House unopposed, or with minimal opposition. And so he likely paid it little mind when Elizabeth Holtzman filed to run against him. After all, she was just a woman.

Which take us to Manny Celler’s other blind spot: women’s liberation and feminism. Big thing in the New York City area in the late 1960s. Not such a big thing with Manny Celler. And in August of 1970, Celler – along with many observers – were stunned when the Equal Rights Amendment passed with 350 votes.

Celler, famously said: “There is no equality except in a cemetery. There are differences in physical structure and biological function.”There is more difference between a male and a female than between a horse chestnut and a chestnut horse.”

And that’s the moment when Elizabeth Holtzman decided to run against him. And unlike previous races, Holtzman’s team took some polls that showed that…well, she wasn’t close. But she was closer than anyone expected at least.

If Celler had just let it be, he’d have likely won the race by double digits. But Manny couldn’t help being Manny, and so through March and April he started giving a few speeches back home in Brooklyn where he repeated his horse chestnut and a chestnut horse" line, thinking that’s what people in his district wanted to hear.

What Celler seemed to not realize was the changing demographics of his district. It was a much younger district than it had ever been – and at 84 in 1972, Celler was already in the 99th age percentile there. He also seemed to fail to grasp is that the 26th Amendment had been ratified, and that people as young as 18 would be able to vote for the first time in the June 20 primary.

And that is how Elizabeth Holtzman beat 50-year incumbent Manny Celler by 671 votes out of more than 31,000 being cast.

(Elizabeth Holtzman on the campaign trail, June 1972)

What did any of this matter to Watergate, you ask?

Well.

As noted above, Manny Celler was the chairman – longtime chairman, as in, considered it his birthright – of the House Judiciary Committee.

Guess which House committee considers articles of impeachment?

Yup.

And as future House Speaker Tip O’Neill would note much later on, if Celler were still head of the House Judiciary, it’s likely that he’d have drawn up an impeachment article or three before the 1972 elections (and before there was much evidence of Nixonian involvement, and had his own party members in the committee revolt and they’d have gone nowhere.

Or worse yet, once there was some evidence of Nixon’s participation, Celler would have rammed through articles without waiting for the evidence to develop, and still would’ve had those articles fade on the House floor without the support of conservative Democrats. Or even if by some miracle they got that, the Senate would’ve had clear cover to vote on party lines to acquit Nixon thanks to the partisan, party line vote in the House.

Probably worst of all: Celler would have insisted on being the one to head an investigation of the break-in, rather than the Senate. And his style – and fading mental capacity – probably would’ve meant a very different, and much better-for-Nixon outcome.

But with Celler losing to Holtzman, his committee chairmanship of Judiciary fell to a guy named Pete Rodino. Rodino wasn’t too much younger than Celler, but whereas Celler was brash and abrasive as part of his brand, Rodino was thoughtful and had an almost gentle air about him. And he saw the big picture. And with him on the chair of the Judicial committee, events were allowed to proceed in an orderly fashion. And as they went, Rodino’s ability to read the political winds told him to let things play out, and eventually the Republicans on his own committee – and in the House – would come around. And everyone in Congress – Republicans and Democrats alike, kind of liked Pete Rodino. He was considered a very, very fair man.

But don’t take my word for it. Take Tip O’Neill’s: “If the impeachment process had gone to the Judiciary Committee under Manny Celler, it would have died there,.”

Or Jimmy Breslin’s: The primary election between Holtzman and Celler could be considered one of the most meaningful elections the nation has had."

Really enjoying this. We just finished watching Gaslit on Starz with Sean Penn and Julia Roberts as the Mitchells. Not knowing much about Watergate, I assumed a lot of the characters were just made to be super crazy/incompetent, especially Liddy, but after reading your telling, maybe they aren’t so over the top after all.

The Quote No One Actually Ever Said (Probably)

“Follow the Money”.

It’s perhaps the most famous quote from All The Presidents Men, but there’s no evidence that Deep Throat ever said. Nor anyone else.

But following the money is exactly what FBI agent Angelo Lano and the two agents assigned to work with him were doing.

It had only taken the FBI veterans a day or two to discover the full identities of all five burglars, even though they weren’t sharing that information and carried no identification.

The thing that really intrigued Lano was the money the men carried – the $2400 in sequential hundred dollar bills. By the 21st of June, 1972, the FBI agent had traced that money to Bernard Barker’s bank account in Miami. And using the investigatory powers of the federal government, Lano was able to do a deep dive on Barker’s accounts at the bank.

What Lano discovered was that Barker had withdrawn the hundreds as a bank counter transaction with a teller. Easy enough, and totally legal. But in checking out Barker’s bank account, he saw huge checks being deposited there. All were bank cashier’s checks. All but one of those cashier’s checks came from a bank in Mexico City, arranged by a prominent Mexican corporate attorney.

And then there was one check that came from a Minnesota businessman, an ex-World War II air ace hero named Kenneth Dahlberg. (Note that name; he’s going to feature prominently later this summer – though I want to stress here that Ken Dahlberg seems like an innocent guy who had no idea what CREEP was using the funds he was bundling for.)

Lano didn’t quite have the goods – yet – to positively conclude that the Watergate burglars had been knowingly paid by the Committee to Re-elect the President. But he was getting pretty close to that.

Money laundering was one of Nixon’s primary skills in politics. He was honestly kind of good at it, for the time.

So one question that’s been asked here – and which has been asked by pretty much anyone familiar at all with the Watergate story is pretty basic.

Why?

By May of 1972, some things had become very clear regarding the national election day coming up in six months. The first of those was that Nixon was going to get his dream opponent in South Dakota senator George McGovern. Every internal poll that CREEP had commissioned showed the Committee that McGovern not only could not win, but might lose to the incumbent president by historical amounts. Heck, not only did Republicans know that they’d crush McGovern, but so did Democrats who saw lifelong, FDR loyalists fleeing their own ticket in droves.

Nixon’s re-election was never in doubt in 1972, and especially not by June of 1972. So what the hell?

To understand that, you can look at a lot of different things…but it all comes back to one thing. Well, really, one person: Richard Nixon.

So if you’re not familiar with all things Nixon, let’s dig in.

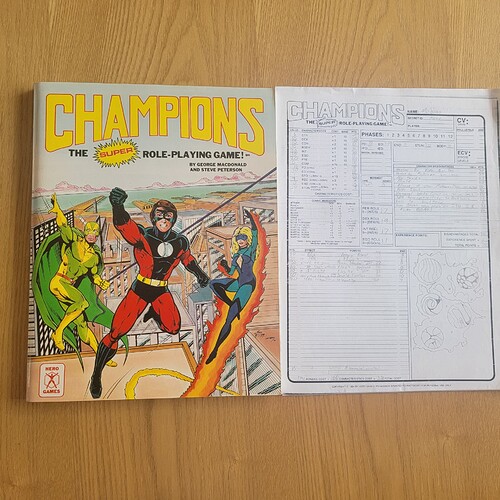

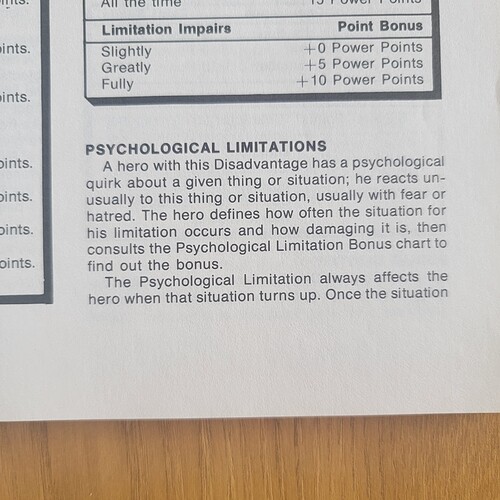

I want to start by invoking an old pen and paper role playing game called Champions. It’s a superhero rpg, where the player characters are all superheroes that each player creates. And in character creation, you can load up your superhero player-character with all sorts of tremendous, almost game-breaking powers…but you have to take “disadvantages” to even out the scales, that potentially weaken your character and maybe even to the point of making the created PC superhero broken.

And that’s kind of what Richard Nixon was.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Nixon is the most consequential political figure in America’s post-war history. From 1952 to 1972, he ran on the Presidential ticket 5 out of 6 elections, and won 4 times. And I’m going to say something that may rankle, but which I think is absolutely true: in many ways Richard Nixon was perhaps one of the most gifted politicians to serve in the White House.

Wait. Don’t egg my car just yet.

His political skill hits on a couple of different vectors. Maybe as much as any other president in history, Nixon had an innate sense for how a huge number of voters were thinking, and knew how to appeal to those voters. He spoke their language, and when he talked – whether that appeal was a good thing or bad thing – those voters flocked to him.

But Nixon also confounded his early critics. He’d made his bones and carried a reputation as a right-wing conservative who was stridently anti-communist. But in his first 4 years in the White House, President Nixon showed what was often a pragmatic side, willing to cut deals to get legislation passed. Which is how we ended up with Nixon establishing the EPA, signing the Clean Air Act into existence, and making Title IX a thing. (Nixon would never be confused with favoring feminists, but he did see value in elevating women in the workplace – to a point. According to Nixonland, Nixon’s administration had the highest percentage of new hires of women into non-secretarial roles in White House history.)

And diplomatically, he didn’t seem at all like the raging, reactionary anti-communist of his earlier days. He and Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev realized almost immediately that they “got” one another. Both leaders were kiiind of OK with the status quo in larger terms. And neither wanted the cold war to go hot, and both knew the other guy didn’t want that, either. And both knew the other guy was going to have to rip into them from time to time to score political points at home. The two leaders seemed to have genuine affection for one another.

And though stuff like that can get lost to modern history, in 1970 it was enormously comforting to come to a realization that a potential nuclear war with the Russians was fairly unlikely…after living with it seeming at least passingly likely for the previous 20 years.

So…all good, right? Well…about those “disadvantages”…

Richard Nixon was an absolute trainload of psychoses. He was as deeply insecure as any man who’d gone into the White House in over a century, maybe since James Buchanan. It was that deep-seated insecurity and inferiority complex that helped him connect to the grievances of white, blue collar workers in the late 1960s.

He was incredibly socially awkward. While Nixon intensely disliked the Kennedys for their politics, he HATED them with the fire of a thousand suns because Jack, Bobby, and Ted possessed such native charm and charisma and seemingly effortless abilities to interact with others. Nixon at times seemed to struggle with the most basic of human communication and niceties. He really had just two close friends he leaned upon.

He was also dangerously paranoid and for a president astonishingly thin-skinned. Anything could be a slight to Nixon, even the inflection of a TV news reporter or anchor; he was convinced that pretty much everyone was out to get him, and convinced that even minor perceived slights were part of a conspiracy to get to him. Nixon kept a series of absurdly detailed enemies lists that even his own close staff couldn’t quite always remember which list header had the worst enemies on.

Even more weird: Nixon seemed almost preternaturally gifted at understanding the concept of proportionality when dealing with antagonistic foreign powers, but seemed baffled by such things in personal relationships. Thus, not only did Nixon keep enemies lists, he meant to strike back at those enemies. Nixon would do things like ask about possibly getting a reporter or editor who had written something uncomplimentary about him fired. He’d ask about getting law licenses revoked, and sic the IRS with an audit on more than a few occasions. Nixon didn’t stop there though; he’d often ask about what could be done to break up the marriage of someone who’d offended him, or if they could maybe plant evidence that a perceived enemy was gay in order to wreck a career.

Nixon’s White House was very different from the White Houses of previous and future presidents. It’s possible that Nixon wouldn’t have recognized most of his own cabinet if he were to have passed them in a West Wing hallway. Because of his paranoia, Nixon surrounded himself with an inner circle, and no other advisors or cabinet members really mattered that much. It was Nixon, his right-hand man Haldeman, his almost right-hand man Ehrlichman…and then also John Mitchell and Henry Kissinger. Sometimes Chuck Colson, sometimes not. Anything requiring presidential attention had to come through one of those guys.

Maybe most dangerous of all was Richard Nixon’s relationship to the truth. He thought of himself as incredibly honest, and believed it. What was actually true, however, is that if Nixon found particular truths to be uncomfortable or unacceptable, he’d perform mental gymnastics to justify to himself why the truth wasn’t the truth, and keep telling himself little lies until he got to a point where he’d fabricated something completely, but had convinced himself of its utter truth. Thus, he easily slipped into untruths and fabulations, all the while believing that he was the real and pious truth-teller.

A by-product of that – and a dangerous one – was that Nixon valued loyalty over honesty in his advisors and White House employees. His administration was filled with strivers who all wanted to work their way towards the inner circle of trust. And the delivery of any sort of adverse news was how you fell away from the inner circle and could never get back. Nixon’s longest-standing and most trusted advisors had all learned that lesson and created an atmosphere where deception, half-truths, and outright lies were the way things were done.

There are a number of theories for why, with a massive lead and an almost assured landslide victory, that Nixon campaign goons would do a high risk/zero reward caper like breaking into the DNC Headquarters at The Watergate Hotel. And it may have been done to score loyalty points to a boss who simply had to know what sorts of mean things his political opponents were saying about him.

Great piece of writing!

A few years ago I went to the bar at the Watergate and the concierge let us tour the room where it happened. I was lit up, so be kind.

I am ready.

Opening to the right page.

As much as I hate the guy, yeah, he totally was.

I believe the modern terminology is caravan of psychoses.

You have a wonderful smile.

+like

That is amazing! I was hoping the analogy was apt. :)

In the mid-80s we stayed at the Howard Johnson’s across the street from the Watergate, had I known they had a bar I would have talked the wife into walking over there.

My Champions character was a lizard man with telepathic powers who could cling to walls.

So basically Nixon then.

Y’know, never thought of that. But, yeah, Tricky Dick the Caped Crusader! Now gotta find me some commies to root out!

What Kind of Day Has It Been?

There have been a lot of consequential and historically important workdays in the life of presidents since the end of World War II. But an argument can be made that no post-war US president had a bigger 8-hour workday than Richard Nixon had on June 23, 1972.

In the morning, in an open to the press and interested public session, President Nixon signed the Title IX Amendment to a US Education act. Title IX banned the use of federal education dollars to any institution that discriminated on the basis of gender or race. That was pretty huge.

And then in the afternoon, on tape, President Nixon did the crime for which he would eventually be forced to resign.

At this point, it’s worth noting that the crime of “Obstruction of Justice” is one that’s really hard to prove and for prosecutors to get a conviction on. It requires the defendant to first know that a crime has been committed that their actions my be obstructing an investigation into. High bar, that. Second, it has to involve clear intent of those obstructing actions. So you can actually have obstructing actions – but if they weren’t intended to obstruct, then not a crime.

That’s a lot of prior knowledge, belief, and intent to prove, and it’s why Obstruction gets threatened more than it gets charged or (especially) convicted.

And with that said, in an afternoon meeting in the Oval Office between HR Haldeman and Richard Nixon…it happened. On tape.

So earlier this week, we talked about some things that would lead to this incredibly consequential meeting. First, there was White House concern that the FBI investigation might turn over too many rocks, and Nixon, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman had discussed – vaguely – some potential reasons why the FBI might wrap up their Watergate investigation with just some limited charges filed against the burglars, Liddy, and Hunt.

One of the ideas that came up was playing on the involvement of Cuban ex-pats who were Bay of Pigs operation veterans. Perhaps, the thought was, if the FBI thought that Watergate was some sort of CIA operation, they’d back off? Hmm. John Dean, make a few calls, plant a seed, see what happens. Almost obstruction, but not really on tape, and not specific enough. Yet.

Then came the story that leaked into both the NYT and Washington Post that the FBI had found the money carried by the Watergate burglars seemed to trace to burglar Bernard Barker’s bank account, in which cashier’s checks of shady provenance related to a Mexico City corporate attorney and a Minnesota fundraising bundler for CREEP had been deposited.

That latter bit provided urgency. The previous bits provided method.

And so in that afternoon Oval Office meeting, HR Haldeman tells the President that his feelers to the FBI have shown that the investigating agents – and their superiors – kind of think that they have indeed stumbled into a CIA operation. So why not use that?

Nixon can be heard on tape agreeing. But then he also asks why (Interim FBI Director) Pat Gray – straight-up Nixon loyalist – isn’t playing ball.

Haldeman: “He wants to. He just doesn’t know how. He needs some help on that from us.”

Nixon surmises Haldeman’s meaning. So…if we could tell the FBI that there’s big resistance from across the river (meaning The White House), he’d be able to wind this thing down, Nixon asks.

Yes, exactly, says Haldeman. But they’ll probably need that to come directly from someone at CIA.

Nixon notes that this could be a snag. The White House doesn’t have a great relationship with CIA Director Richard Helms.

But both men then seem to realize that Deputy Director Vernon Walters – two weeks on the job and just appointed by Nixon – might be leveraged into making that FBI call.

Nixon agrees. That would be the way to do it.

Then the two men discuss that’s preferable to shut down the FBI investigation than to try to get to potential FBI interviewees and get them to tell the right story. More general agreement between the two men. This is the strategy they’ll pursue, and arrange a White House meeting with Walters ASAP.

And in that June 23rd taped conversation, Richard Nixon and HR Haldeman satisfy every criminal law statute requirement for obstruction of justice. 24 months later, when one of Nixon’s lawyers listens to this tape, he’ll call it the “Smoking gun” tape, by which it will become known down through history. The tape would be publicly released on August 5, 1974. Nixon would resign on August 9.

Minor correction: June, I believe.

This is the thing I look forward to reading most every day.