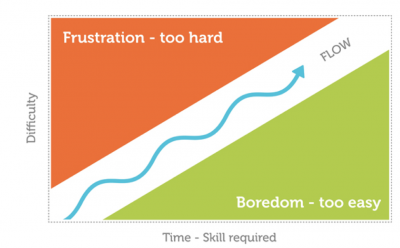

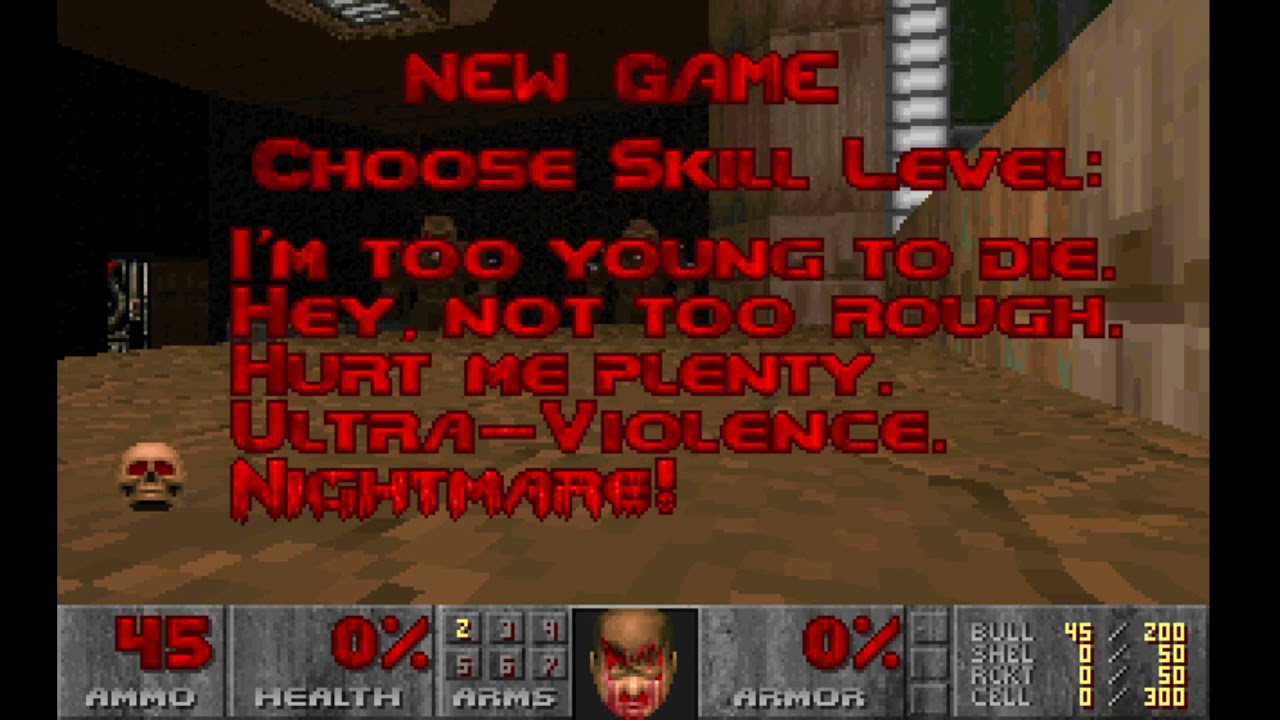

I’m reminded of this principle: learning is necessary for fun. A successful game design teaches players how to use its systems to overcome its challenges. The player who fails without learning becomes frustrated and quits. Some can’t or won’t learn or lack essential skills or need extra help (easy settings, cheats, accessibility), and some learn quickly and want more difficulty.

Because the gameplay is supposed to be fun. Players who don’t want to engage with the tools and obstacles probably picked the wrong game (or hobby), or they do need to change the difficulty, or else they’re struggling against bad game design.

Market forces. Developers want the widest possible appeal for sales with as much of the game to be reachable as possible to avoid wasting resources building unseen content, and nobody can afford to alienate interested players when there is so much competition. AAA budgets especially require compromises because universal balance for all players is generally not possible.

“Making a game for everybody is the same thing as making a game for nobody.” -Soren Johnson, reflecting on the development of Spore.

Their goal is usually not to defeat or frustrate the player. It’s more like mentoring. Players must decide how hard to push themselves based on what they want from the experience. The “losing is fun” idea (as in Dwarf Fortress or AI War) is insightful and valuable to some of us, but not all.

I’m in favor of what I call “geographic difficulty”, where most content is accessible to the player in an open-book or open-world format, rather than gating difficulty behind play time or progression or options. Think Ghost Recon Wildlands or Crusader Kings 3, where the player can tackle whatever interests them or feels appropriate. A game world can have guidance and warning signs without blocking the player’s path. The difficult content can be there to entice players even if they opt out.

A downside to this may be choice paralysis, where having too many options becomes a disincentive. It’s a bit like the map-marker spam problem, as having some absurd checklist to optimize before you play feels much worse than just exploring.