I was living in Northern VA when everything unraveled and Nixon resigned, so I have some pretty strong memories of it being constantly in the news. The hearings were the lead story every night on the news, and we took the WaPo so it was front page stuff every day. The weirdest thing I remember was that my older brother and some of his friends were in a crowd outside the White House the night the news broke that Nixon would resign.

Years later, in the mid-80s, I was working in the DC area and would occasionally drive by the Watergate. It still had a sort of symbolic presence, really.

We stayed in the Howard Johnson’s across the street from the Watergate in the late 80’s and I thought about Nixon every time I looked out the window.

Sorry folks! Busy weekend here, but lots of stuff I wanna get to. So let’s backtrack a bit.

The Coronation

Ok, so yeah, technically not really a “coronation” as such, but about as close to it as you can get when Richard M. Nixon is sworn in for his second term on January 20th, 1973. Whether the country is in a better place than it was 4 years ago is a debate beyond the scope of anything I’m typing about. But what is undeniable is that the vast majority of voters in America believed the country was in a better spot than it had been in. And Nixon had been a part of a lot of that. He was absolutely a highly skilled politician.

His inauguration, then, is a celebration of all that, of the historical landslide victory, of America again seemingly ascendant (those oil prices though!). There are literally hours and hours of coverage of the inaugural weekend (the 20th of January was a Saturday) on network TV news. There are thousands of words and gigantic chunks of column inches on front pages of newspapers across the country celebrating the inaugural…and the term “Watergate” shows up (per some Brookings estimates) occupying about one-half of one percent of all of that. (And when it does show up, frequently it’s as this thing in the past.)

The person who was given the task of heading up the Inauguration planning was Jeb Stuart Magruder. He’d come into the Nixon orbit as a special assistant to the president for Nixon’s first term, and then graduated to Deputy Campaign Chairman for the re-election serving just under John Mitchell at CREEP.

And the thing to take away from any Watergate discussion is that Jeb Magruder was possibly the most unlikeable character in a criminal saga with PLENTY of unlikable characters to pick from. Magruder was a slick, crawlingly ambitious and malevolent presence in the campaign. From descriptions of not only his co-workers but also from history, he seems to have combined all the worst traits of Pete Campbell from Mad Men, the middle manager guy in RoboCop, and Grima Wormtongue.

It was Magruder who was instrumental in hiring Liddy and Hunt in the first place, and once they had their dirty tricks team in place, Magruder was the guy who served as the go-between between the group and Mitchell and Haldeman. And it was Magruder who had delivered the news to Liddy and Hunt that the bugs and phone taps planted in their FIRST Watergate break-in on May 28 hadn’t gotten any information. Magruder was the one who is most likely to have suggested the second, ill-fated break-in on June 17.

And, for now, Magruder is clean as a whistle. All of the Watergate 7 are playing ball with the White House, and the scandal hasn’t (yet) gone past them. But that dam is starting to show some weaknesses.

1,461 Days

When Nixon’s top aides and cabinet members reported to work on Monday, January 22, 1973, they found a nice surprise awaiting them.

President Nixon had gifted each office with an inscribed, ultra-fancy desktop calendar. On each, Nixon had engraved the following:

Every moment of history is a fleeting time, precious and unique. The Presidential term which begins today consists of 1461 days – no more and no less. Each can be a day of strengthening and renewal for America; each can add depth and dimension to the American experience. The 1461 days which lie ahead are but a short interval in the flowing stream of history. Let us live them to the hilt, working each day to achieve these goals.

Note to self: it actually might indeed be “less”.

The Would-Be Consigliere

John Dean in 1973 is what you’d call a “climber”. Ambitious to a fault, he’d gotten a taste for politics as legal counsel for the campaign advising Mitchell and Magruder at the top of that food chain. When everything went down over the summer, it was Dean who prepped CREEP staffers before their depositions with the FBI or DC prosecutors. In fact, Dean sat in on a number of those interviews and took fastidious notes.

And Dean got a lot of credit for managing to keep the Watergate prosecution to just the 7 men who were currently standing trial in Judge Sirica’s courtroom. That got him the attention of the White House, and throughout the fall it was Dean who briefed the President and his advisors on Watergate (much more so than the President’s official counsel, Herb Kalmbach, and even Nixon’s “Special Counsel”, the always-devious Chuck Colson).

Heck, Nixon even remembered Dean’s name. That was something.

And so Dean wanted nothing so much than to be in the President’s inner circle, and here in February of 1973, he’s there. He’s become the de facto coordinator of White House strategy on Watergate. Everyone hoped that would be a short-lived job. It’s turning out not to be the case.

In fact, as far as Dean can tell, things are starting to spiral out of control, and it’s all over the god damned money thing.

A Hopefully Short Digression On The God Damned Money Thing

The money thing would be one problem if it was just the slush fund of cash that someone had paid the Watergate burglars from. Just the existence of that money, and the lack of accounting on it? Kind of a big deal, but probably pretty much an eventual nothingburger in the grand scheme.

So it’s not so much that. It’s the ongoing invisible payments. That’s the real money thing that’s killing Dean and keeping him up nights. One of the defendants, Sturges, has already told Sy Hersch that the Watergate Seven are all still receiving payments. And so that’s bad. But also there are poorly sourced stories in the media that the Seven will get $2,000 per month for their families while they’re incarcerated.

And the thing of it is, when Dean goes to Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Colson, or Mitchell or Magruder to find out if that’s real, they all tell him that it’s ridiculous…but they also don’t really specifically and categorically deny it, either. Dean is getting frustrated throughout January, because he can’t get a straight answer from anyone.

And the American public is getting frustrated. The ongoing money trail and payoffs are obvious and clear to see. And it’s also clear that the prosecution team headed by Earl Silbert aren’t interested in pursuing the money angle.

Which is pissing off Judge Sirica.

More and more, once Silbert is done with a witness on the stand, Sirica interrupts and asks the witness to stay. And then the judge himself starts grilling the witness, and it is always about money. Where’s it coming from? Who controls it? Who approves it?

At first, the public thought they had another Julius Hoffman on their hands, but quickly the tone shifts. Americans are frustrated that Silbert keeps ignoring the money trail. And Sirica is their voice, because he’s clearly annoyed, too.

Silbert’s Fall Guy

And so as the trial enters February of 1973 (50 years ago, don’tcha know), lead prosecutor Earl Silbert realizes that he can’t just stick to the 7 men on trial. He’s got to at least make it look like he’s pursuing the cash disbursements.

And as he’s calling witness, he thinks he’s got an angle on that.

But first, he’s got Jeb Stuart Magruder on the stand. Good ol’ Jeb! Under oath, Magruder (who is at least as guilty as any of the seven men on trial, and maybe more guilty) denies ever having known anything about Watergate. No siree, Jeb knows nothing about any such goings on.

At the defendants table, G. Gordon Liddy hears Magruder’s testimony and appears to be on the verge of laughing out loud. He seems greatly amused by the spectacle.

And then Silbert calls CREEP Treasurer Hugh Sloan to the stand. Sloan is visibly nervous answering Silbert’s increasingly aggressive questions about the money in the campaign headquarters. Silbert sees an opening here. Silbert goes in for the kill. To his ear, Sloan sounds guilty as hell. He may give up enough to warrant prosecution, even.

At the defendants’ table, Liddy takes all of this in, and appears to be ready to fall out of his chair laughing. Sloan is the ONE guy at CREEP who was a total boy scout. Liddy and Hunt had to plan to work around Sloan to keep him from discovering what they were up to. And Sloan was the one guy with a conscience in CREEP who resigned when it was obvious that the Watergate break in had a connection to the Committee.

Sirica’s none too impressed with Silbert here, either. Sirica’s read the FBI interviews with Sloan, as well as Sloan’s grand jury testimony (both of which were fully available to Silbert as well, it shoudl be noted). And Sirica knows that Sloan is completely innocent and that innocence makes him nervous in the face of aggressive testimony.

(Side note: Earl Silbert was a rising star in the DOJ and prosecutorial circles at the time. His baffling conduct – whether personal idiocy or part of a cover-up – during the January and February Watergate trial in 1973 would fully derail his career. He’s spend the rest of his life in private practice, loudly proclaiming to anyone who’d listen that he’d done a much better job prosecuting the Watergate case than anyone ever gave him credit for.)

Eventually, Silbert relents, once Judge Sirica starts apologizing to Sloan for the conduct of the prosecution. And so things proceed with no resolution that the public will accept for the god damned money thing. Which keeps looming larger and larger.

And so now we’re back to John Dean, who wakes up in the first week of February to see that the President’s popularity has dropped 13 points since it sat at 68% before the Inauguration. There’s no widespread belief that the White House was involved in Watergate…but people sure do seem to want someone further up the food chain than Liddy or Hunt to take the fall over the money.

Next up: The Simple Country Lawyer enters the picture.

The Committee

Things in 1973 moved fast. As the trial of the Watergate 7 (which was actually just the trial of Liddy and McCord, the latter of whom had still not gotten a deal offer he was happy with) headed towards a conclusion in January, things seemed to get exponentially worse, public opinion-wise, with each passing day.

And there was growing political pressure. More and more, the courtroom proceedings in Judge Sirica’s courtroom felt to the American public like bad theater. Sirica would push and push, but no headway would be made, stonewalling continued, and judging by the mood on national editorial pages and in the evening network news, the general feeling was that the case would be closed with 7 convictions and so many questions would go unanswered.

The Democratic Senate Majority Leader, Mike Mansfield, was most displeased about all of this. Not so much the lying and stonewalling and illegalities from CREEP. No, Mansfield was upset because building political pressure was finally going to force him to do something regarding Watergate. Mansfield only had a hunger for debate and discussion in the Senate. He hated the idea of rocking the boat. Thus, Mansfield had resisted calls to convene an investigatory committee in the summer and fall – and had short-circuited an attempt by Ted Kennedy to do an investigation in July and August.

But now Mansfield couldn’t ostrich Watergate away. And so he let it be known that there would be a senate investigation into Watergate by a select committee. And in early February, that committee was voted into existence by a 77-0 unanimous vote in the senate.

And though Mansfield had dragged his feet on the Senate Committee, by the time he named it he actually kind of knocked it out of the park. The committee would be headed by North Carolina Democrat Sam Ervin. Three other Democrats included Hawaii’s Daniel Inouye. There would be three Republicans as well, including Connecticut’s Lowell Weicker and Tennessee’s Howard Baker. Because Ervin was the head, it would become known to history as the Ervin Committee.

The thing of it is, if you were to poll the Senate for the most honest, high-integrity senators in the chamber, at least 5 or 6 of them would’ve been on the 7-man Ervin Committee. So that at least boded well for them from the get-go.

Ervin didn’t expect much from the Committee he headed. He figured it would be something of a snipe hunt. But he and Baker (the ranking Republican minority member on the committee) brought on two fantastic attorneys to serve as lead counsels – for the Democrats, it was Sam Dash. For the Republicans, it was a Tennessee friend of Baker’s, a tall, telegenic lawyer y’all may have heard of: Fred Thompson.

The White House also (in general) didn’t expect much from Ervin and his committee. The general attitude in the West Wing was that all of this would blow over “In a few weeks”.

One guy was worried, though: the White House point man on Watergate: special counsel to the president John Dean.

Dean knew some things. First, he knew that Ervin wasn’t the laid-back, easy-going, syrupy southern gentleman he liked others to think of him as. Ervin was a Harvard Law grad, and sharp as a tack. (He was also a segregationist who’d put his legal expertise to work defending Jim Crow laws, so, y’know, Milkshake Duck and all.)

But the other worry that Dean had lay with the integrity inherent in the Ervin Committee. Lowell Weicker was a “Rockefeller Republican”, a member of the rapidly dwindling liberal wing of the Republican party. And Baker was a loyal Republican, but Dean knew that Baker was unlikely to be willing to go too far in defending some of the conduct that Dean had seen in the White House.

And Dean’s head was not in a good place anymore. His dream job defending and representing the White House on Watergate was becoming a nightmare.

John Dean’s Barbecue

It’s early February 1973, and there’s finally a break in the cold DC weather. And so White House counsel John Dean – the clearly-recognized leader of the Administration’s Watergate strategy and response efforts – is taking the opportunity to fire up the grill in his suburban, Northern Virginia back yard.

It’s been a rough coupe of weeks for Dean.

As stated, he originally loved the idea of being the go-to guy on Watergate for the White House and for Nixon. It put him right into the “Inner Circle” with Ehrlichman, Haldeman, Colson, and others. They deferred to him. He’d report on what he was seeing and give recommendations, and then everyone discussed. Very heady for a young lawyer.

But in the last week or so of the trial of the Watergate 7, he’d noticed something that was starting to scare him. A lot. Since the Watergate break-ins, and on through the election and then into the trial, the general strategy was to keep investigators from diving too deeply past the 7 men who’d been accused. The strategy was to keep investigators away from finding out too much about the “slush fund” of cash the campaign had, and by extension maybe preventing them from discovering any culpability by Mitchell and Magruder at CREEP.

And then also, the worry was that an investigation might ask uncomfortable questions about the Kissinger wiretaps of the Washington press corps after the Cambodia bombing leaks. Or to keep them off of the Pentagon Papers story, and the break-in by Liddy and others of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office.

Thus, the tactic was to stonewall and give no information of any value to investigators. And that worked very well, to a point: it meant that only the 5 burglars, along with Hunt and Liddy, were indicted for Watergate.

But what Dean had noticed is this: Judge Sirica, the press, and the seeming mood of the country had subtly shifted as the trial wound down. It became frustratingly clear to all that nothing would be discovered in the trial to explain why the hell the DNC headquarters at Watergate had been bugged. But failing that, it raised new questions. The lack of answers or explanations pointed to the existence of some kind of cover-up to Sirica, the media, everyone.

And so in those final days of the trial, that’s what was scaring the hell out of John Dean. If tangible evidence of a coverup (and thus obstruction of justice and conspiracy to obstruct justice) emerged, that was going to sink a lot of ships in the West Wing. Magruder would be implicated. Mitchell, the former Attorney General and campaign chair? He’d go down too. Probably Colson also. Countless middle-men at CREEP would be in trouble. Maybe even the two second-most powerful men in America as well: Haldeman and Ehrlichman.

John Dean poured lighter fluid onto his grill on that early February evening in 1973. He realized that Interim FBI Director L. Patrick Gray would also go down. Gray had been nominated for the full-time position to take the interim tag off him. But his nomination was already seemingly sunk – in routine questioning by the Senate during his confirmation hearings, Gray had let slip that he’d been feeding interview sheets and reports by investigators to John Dean at the White House. That admission (which had outraged even Republicans on the Judicial Committee), in addition to ensuring that Pat Gray would never get confirmed, also put John Dean’s name into the national consciousness for the first time.

And Dean knew something else about Gray. In the days just after the break-in, E. Howard Hunt had instructed Dean to remove five leather-bound, expensive notebooks from the safe in Hunt’s office. Hunt at least believed the contents of the notebooks were radioactive. Dean presumably read them all, and within the week gave the interim FBI Director three of the notebooks, with instructions to Gray to hold them…but not release them. It was a canny, lawyerly trick. It allowed Dean to say to FBI investigators that he’d turned over everything in Hunt’s safe to the FBI, without necessarily perjuring himself.

But whatever was in the three notebooks given to Gray, he seemed to concur with Hunt. They were toxic and would implicate many others. And so the acting Director of the FBI burned the three notebooks in the summer of 1972, erasing whatever evidence might have been in them.

There were 5 Hunt notebooks, though. And many Watergate historians have pointed out that if Dean only turned over 3 of them – and then Pat Gray thought the contents of those 3 were dangerous enough to destroy them – then the two notebooks that Dean had kept must’ve been the evidentiary equivalent of Chernobyl.

In Judge Sirica’s courtroom, even without the benefit of evidence such as might’ve been found in those notebooks, Liddy and James McCord were found guilty of all charges after just 90 minutes of jury deliberations. (The other 5 indicted men had already pled guilty and were standing with those pleas.)

Sirica – in setting sentencing for March 23 (mark that date down, y’all) – noted that he hoped the newly formed Senate committee on Watergate would have more luck finding those involved, tracing the money, and exposing participants in any potential obstruction of justice.

Those words chilled John Dean to the bone.

And so on that February weekend in 1973 in his backyard, John Dean was spritzing lighter fluid all over those remaining two Howard Hunt notebooks before setting them ablaze. In so doing, Dean mused, he’d crossed any remaining blurred lines from being an advisor and counselor on Watergate to being an active participant in obstruction of justice and criminally culpable in a coverup.

Hey, I’d be born exactly five years later! Talk about an important date for American democracy!

Nice installment as usual, trig. I thought Dean would be roasting some burgers or weenies on his grill, and never expected it to be evidence.

This wanton, deliberate destruction of evidence by senior officials reminds me of nothing so much as the destruction of CIA interrogation tapes under Porter Goss, Jose Rodriguez and Gina Haspel. None of them ever faced legal consequences for it, either.

Yeah, in his memoir (which alternates from having some terrific insights on Watergate and the administration to having eye-rolling, self-serving “only innocent man in Shawshank” bits that are hard to take) Dean mentions that moment of burning the notebooks as the moment when he realized that he was committing big boy, jail-able crimes.

And it should be noted that Dean lied to both the FBI investigators and then Earl Silbert’s prosecution investigators about his having the notebooks, and then later – once he had served his legal bit and was out of jeopardy – allowed that “Oh, yeah, I guess I had them.” He also has at various times said he forgot what was in them, or that he never read them. We’ll likely never know what was in them.

Back then lying was a big deal. Now? Not so much it would seem.

This is where we are now.

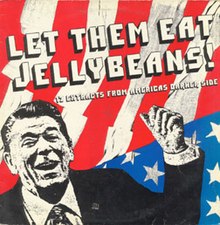

Thanks Reagan.

Guys, I figured out who @triggercut is–David Halberstam (nevermind that he died in 2007). I just read The Best and the Brightest (see the book thread for my review) and I gotta say that the writing style here has me pretty much convinced that this is Halberstam’s next work on Watergate.

To be clear, I very much mean this as a compliment!

High praise indeed! The Breaks of the Game is the finest book on basketball one could ever read.

A nice compliment, but David Halberstam wishes he had such good taste in music, movies, and games.

He also wishes he was still alive.

LOL, thanks guys, but yeah, about the only thing I’ve got on Halberstam is a body temperature above ambient. :) (And there have been times in the last 10 days where even that was up for debate.)

But god I love Halberstam. I’ve read so many of his books – re-read them, if I’m being honest. So yeah, it’s totally likely that some partial elements of his style may have unconsciously rubbed off on me. I assure you though that any similarities are the historical version of bad karaoke singing.

This is absolutely what I picked up on, yeah. :)

Edit: though thankfully your parentheticals are limited to a sentence at most.

OK, in a week, we have two of the biggest things to happen (so far) since the break-in itself occurred in June of 1972. But there’s a bit of table-setting to do for that.

Last Clear Chance

There’s a scene in the film Apollo 13 (modeled off real life, I suppose) where Mission Control in Houston instructs the crew aboard the suddenly-damaged command module to shut off the react valves to the fuel tanks. Although my fellow space geeks will know that this procedure was ultimately ineffective, it still represents a key moment in the film.

Tom Hanks as Jim Lovell solemnly intones “Gentlemen, we’ve just lost the moon.” It is at that point that everyone – in Houston and up in space – understands that the mission has changed. They’re no longer going to the moon; the goal is now to get the three men aboard Apollo 13 home safely. It is a point where everyone involves snaps clear to recognize the seriousness of the situation at hand.

There’s a similar moment for the Nixon administration, about 50 years ago in late February/early March of 1973. There’s a meeting in California, at the La Costa Resort in Carlsbad (Haldeman and Ehrlichman BOTH own suites at the resort). All the big players in the White House and Watergate are there. There’s a sense that things might be getting pretty serious. Nixon’s poll numbers are skidding, and more and more, Watergate is a key story in the nightly news. The President is there. Haldeman and Ehrlichman are there. Colson is there. Various campaign seniors are there.

And three things come out of this meeting that are really important in understanding how things go sideways in the coming months. But overall, understand that there’s a principal in determining fault in vehicular accidents: everything else being what it is, the driver with the last clear chance to avoid the accident may be responsible for it.

The meeting at La Costa is the last clear chance for the Nixon presidency. It should be the moment when someone in charge does the equivalent of telling everyone else “We’ve lost the moon.”

But that’s not what happens.

So. Meeting. La Costa. Everyone’s sitting beside a pool, having drinks. Chairs and tables are pulled up. And John Dean is asked to speak first, to give the current lay of the land.

And Dean doesn’t mince words. He tells everyone that the newly formed Senate Watergate Committee is no joke. Lead counsel for the committee is Sam Dash, and he is good at what he does, and he and the committee will have subpoena powers that may be unlimited.

And also, Dean says, Dash isn’t focusing on the break-in anymore. He and the Ervin Committee are focusing completely on the cover-up. They suspect that crimes like obstruction of justice and conspiracy to obstruct were committed.

John Dean looks around at everyone out on the pool deck at the resort so they understand – everyone sitting there has potential exposure to criminal charges. And Dean lays out those potential charges and consequences, telling every man there (they’re all lawyers, but it helps to reinforce it) that at minimum, anyone convicted of these crimes will do a year or more in prison.

And so that’s the first thing. John Dean tells everyone at this meeting, essentially: “There is a good likelihood they’re coming after you, and if they can discover that you blundered into criming, they’re going to put you in prison.”

So that’s an attention-getter.

And after much animated discussion, John Ehrlichman finally gets the floor to speak. Ehrlichman lays everything back out to Dean, just to be clear. And the Ehrlichman notes that if the 7 men convicted in the break-in and awaiting sentencing in March continue to be silent…it’s unlikely that the Ervin Committee investigation goes anywhere.

He looks at Dean. “Would you say that’s correct?”

Dean thinks it probably is.

Ehrlichman then asks the billion dollar question: how likely are these 7 men to stay silent? What can be done to ensure their continued silence.

That is a thornier question. Dean and Colson both mention that the 7 men convicted have been constantly increasing their demands for their continued silence. More money. Job guarantees. Family security.

But most of all, Dean notes, what some of those 7 guys want most is a presidential pardon. Pardons would guarantee that all 7 maintain their silence.

And so that’s the second big thing. The best way to keep the Senate Committee at bay is to ensure the silence of the 7 men convicted in the break-in. And the best way to ensure that silence is presidential pardons.

Which is when Nixon himself speaks up. He feels incredibly sorry for these 7 men, who likely thought they were acting in the best interest of their country. But with that said…no pardons. Not for those 7 men, and not for anyone having anything to do with Watergate. Period.

Nixon’s words cast a pall on the gathering. For Dean they’re not unexpected; Dean’s been working on trying to get the president to come around on pardons for 3 or 4 months at this point, but after initially seeming open to the possibility, Nixon has been a firm “no” since after the election. Nixon tells Dean – and anyone else who asks – that pardons for the Watergate burglars will put his administration on the back foot for years. They’ll be fighting congressional investigations and battles in court for the entire 4-year term. It’ll mean the Republicans will get slaughtered in the '74 midterms.

No. No Pardons. They’ll mess up all the grand plans Nixon has for his second term.

And yes, that’s the moment where mission control tells the Apollo 13 to shut down the react valves, and the guys in the capsule say “The hell we will. Let’s just see if we can make it to the moon anyway.”

So let’s recap the meeting at La Costa:

-

John Dean tells All The Presidents Men that they are potentially targets of the Senate Committee investigation, and that if they’re found guilty of participating in the coverup, they’re likely to do not insignificant jail time.

-

John Ehrlichman points out that the best way to ensure that the Senate Committee investigation goes nowhere is to ensure the silence of the Watergate 7, and the best way to get that silence is to offer pardons.

-

President Nixon tells everyone that pardons are off the table. For the Watergate 7, and for anyone else.

Yeah. That is three bitter tastes that make each previous ingredient taste worse.

Popular historian Stephen Ambrose wrote a 3-volume biography of Nixon which has some issues, but one thing Ambrose did do was listen to more White House tapes than anyone else. And Ambrose traces a direct line from this La Costa meeting to the unraveling of the coverup – he called it a high-stakes prisoner’s dilemma. If the White House senior advisers had made a plan together as a unified group and stuck to it, it’s possible – maybe probable – that they’d escape Watergate unscathed.

But every man at that meeting is a lawyer. And every man there has heard John Dean say that they could be in serious legal jeopardy, and then heard Nixon say “No pardons”. And so from this moment forward, it basically becomes a growing case of every man for himself.

La Costa represented what was probably the last clear chance to save the Nixon presidency. They bungled it badly. And so the next 15 months will become a shitshow unprecedented in US political history.